Eastern Highlands

Eastern Highlands in the Flora of Victoria system (Conn 1993) comprises the Highlands-Southern Falls and Highlands-Northern Falls regions from the current system of bioregions of Victoria.

Location

This region extends down from the higher-altitude Snowfields below 900—1300 metres to an elevation of about 200 metres (adjacent to the Midland Region in the north and the Gippsland Plain in the south). The wet sclerophyll forests below the Eucalyptus delegatensis community are included in this region. However, it was not possible to circumscribe this region accurately by a generalized and simplified boundary. The highly dissected and rugged landscape results in the development of an extremely complex mosaic of floristic communities. The western limit of this region is geologically (and floristically) defined by the position of the eastern limits of the Newer Volcanic basalt plain (of the Victorian Volcanic Plain). These two regions adjoin at Kilmore East and just north of Yan Yean (between longitudes of approximately 145°00’ and 145°05’E). In the north-east this region is continuous with the Southern Tablelands (of New South Wales), whereas, in the south-east it is juxtaposed with East Gippsland (refer to the latter region for a description of their common boundary).

Major grids N, R, S, T, V and W. Approximate area 28 666 km2.

Major landforms

The basic physiographic structure of the Eastern Highlands is best considered in conjunction with that of the Snowfields Region as the important formative geological events are common to both regions. The two regions are characterized by the uplifted and dissected remains of ancient erosion surfaces. Mountains composed chiefly of volcanic rocks (e.g. the Baw Baw and Buffalo Plateaus, the Strathbogie Ranges and upper catchments of the Yarra, Latrobe and Goulburn Rivers) are the result of exposure and continued erosion of intrusions formed during the Devonian period. The majority of the Eastern Highlands and Snowfields Regions are, however, the result of more recent (Tertiary) uplift and subsequent deep dissection of Silurian, Devonian and Carboniferous sediments. Small areas of basalt exist but these are largely confined to the Snowfields Region as cappings on some of the higher mountains (see also Douglas, this volume).

The soils of the region are complex. Typically, shallow soils occur on ridges and on steep upper slopes. However, fertile loams and earths are typical of much of the higher-rainfall mountains (Gibbons and Rowan, this volume). A typical profile has a thick and loose litter layer overlying a dark-brown friable loam with strongly developed fine structure. With increasing depth, the colour initially becomes paler, then usually more reddish or stronger brown, and textures change to clay loam or light clay (Anon. 1973a). Very fertile loams are associated with basalt (particularly in the Silvan–Wandin area).

Climate

Topographic variation results in the climate varying greatly within this region. In general, the amount of rainfall increases and the temperature decreases with increasing elevation. This region is one of the highest rainfall areas of Victoria (ranging from about 770 to at least 1500 mm per annum). The region experiences a temperate climate, with warm, dry summers (January or February being the driest months, with 40–90 mm per month) and cool to cold winters (May to July usually being the wettest months, with 150–180 mm per month). Only the highest and wettest plateaus receive more than 50 mm per month in summer. In general, the rain-bearing winds are westerlies, north-westerlies and south-westerlies. Topographically-induced rainshadow areas occur on the leeward (eastern) side of mountain ranges. Light snowfalls occur fairly regularly during winter above elevations of about 750 metres (e.g. Mt Cudgewa, Mt Donna Buang, and Mt Strathbogie). The summer mean maximum temperatures can be quite high (about 22–30°C) and winter mean maxima vary from 7°C to 28°C. Minimum temperatures can vary greatly, and are influenced by topography (e.g. aspect, depressions and valleys). The summer mean minimum temperatures vary from 7°C to 16°C and winter mean minima vary from –1°C to 4.5°C. See also ‘Climate of Victoria’ (this volume).

Vegetation

Cool temperate rainforest

Closed-forest occurs as disjunct communities throughout the southern central highlands of this region. The community is dominated by one to three species of trees to a height of about 42 metres. Nothofagus cunninghamii is the dominant species of the community in this region. Atherosperma moschatum is subdominant (rarely exceeding 23 metres in height) to Nothofagus cunninghamii or Acacia melanoxylon. Acacia dealbata, Coprosma quadrifida, Hedycarya angustifolia, Pittosporum bicolor and Tasmannia lanceolata are common shrubs to small trees. Lianes are rare or absent. The moist to wet, protected gullies of the cool temperate rainforest support a species-rich fern flora. For example, Gullan and Walsh (1986) record thirty-four fern species from cool temperate rainforest in the Upper Yarra Valley and Dandenong Ranges (also see Gullan et al. 1979). Of the ferns, Blechnum spp. (e.g. B. fluviatile, B. nudum, B. wattsii) and Dicksonia antarctica dominate the understorey. Cyathea australis and Polystichum proliferum are also common. The filmy ferns, Hymenophyllum cupressiforme and Polyphlebium venosum are also abundant. Several epiphytic ferns are common (e.g. Asplenium bulbiferum and Microsorum pustulatum). Bryophytes and lichens are common on tree-trunks, fallen logs and rocks (Howard & Ashton 1973, table 1).

On the Australian mainland, the principal areas of cool temperate rainforest are found only in East Gippsland, the Gippsland Highlands, Wilsons Promontory, the Otway Range and in this region. The last four regions support rainforests dominated by Nothofagus cunninghamii, whereas this species is absent from East Gippsland. The distribution of cool temperate rainforest within Victoria is given by Seddon and Cameron (1985a, and 1985b). Busby (1987) proposes that the former distribution of this community was more extensive than is now observed, but that recolonization after glaciation has been prevented by recurrent fires. Also, the opportunity for recolonization is reduced in Nothofagus because the capacity for this genus to disperse (seeds dispersed by gravity) is less relative to that of Atherosperma (seeds wind-dispersed).

Cool temperate rainforest chiefly occurs along wet montane rivers and gullies, and more rarely on sheltered mountain slopes and plateaus. In this region, it can be found at the following scenic reserves: Mt Donna Buang (Figure 6.18), Cement Creek, Mt Victoria, Myrtle Gully, and Cumberland (all localities are near Melbourne).

Wet forests

Tall open-forests dominated by Eucalyptus regnans are widely distributed throughout much of the region below elevations of 1300 metres (more commonly below about 950 metres). Eucalyptus delegatensis (mostly associated with vegetation of the Snowfields Region) forms tall open-forests (montane forests) above elevations of about 950 metres. Similar forests are occasionally dominated by Eucalyptus nitens. The understorey (up to about 7 metres high) is dominated by shrubs, with the ground-layer consisting of ferns, grasses and herbs. Ashton (in Groves 1981) provides a general overview of the tall open-forests in Australia.

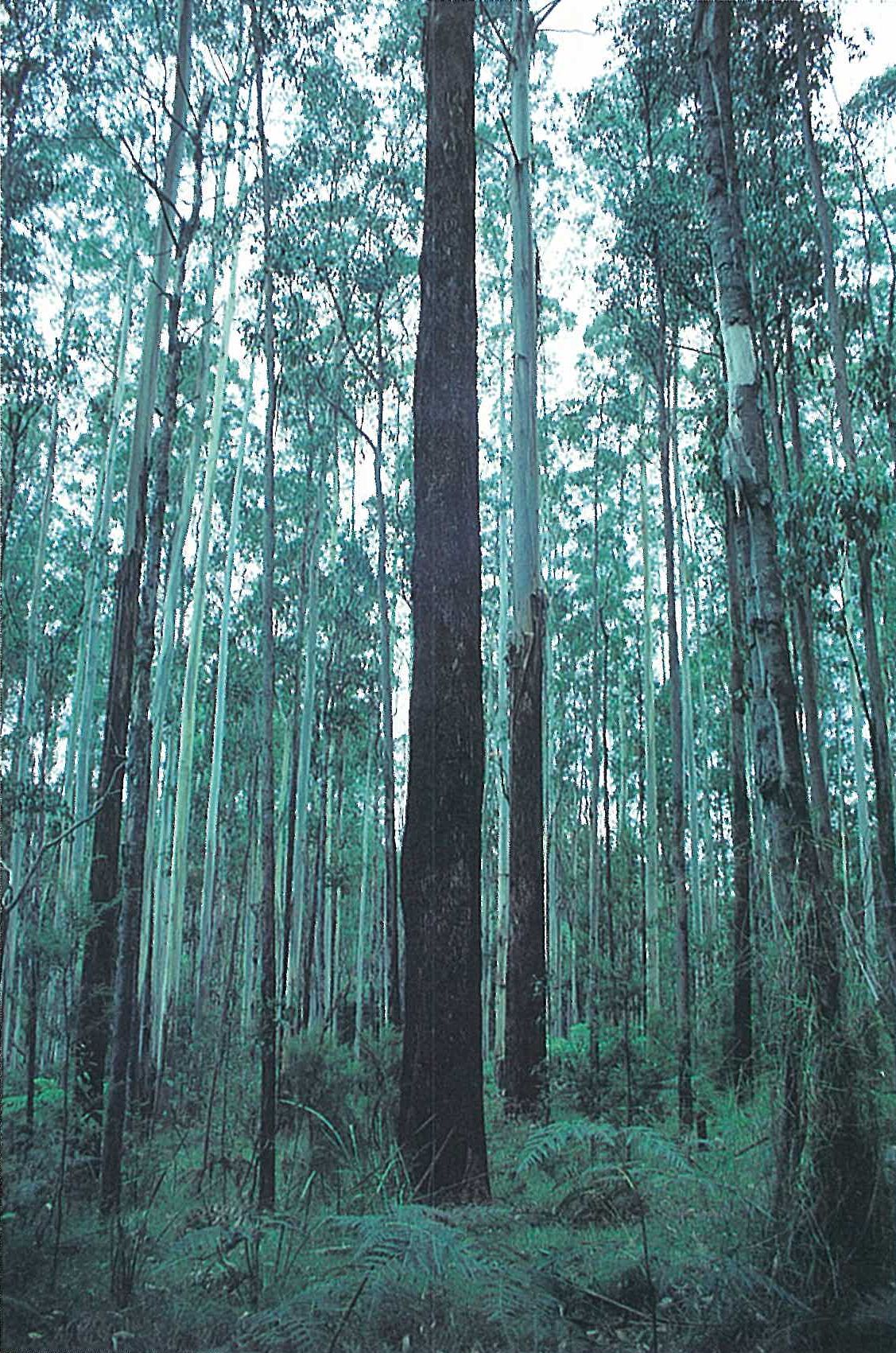

Eucalyptus regnans forests

Eucalyptus regnans (Mountain Ash) occurs mostly as pure stands, but may occur in association with other eucalypts (such as E. cypellocarpa, E. nitens, E. obliqua and E. viminalis. Eucalyptus regnans frequently forms natural hybrids with E. obliqua (Ashton 1981), and occasionally with E. macrorhyncha (Ashton & Sandiford 1988). These forest are very tall with E. regnans (the world’s tallest flowering plant) reaching heights of 40–95 metres; however, many of the tallest representatives have now lost their tops (e.g. ‘Valley of the Kings’, near Cumberland Falls). The understorey is characteristically three-layered. Tall shrubs and small trees dominate the upper stratum up to 30 metres high (e.g. Acacia dealbata, Bedfordia arborescens and Pomaderris aspera), the middle stratum consists of smaller shrubs (e.g. Cassinia aculeata, Coprosma quadrifida, Correa lawrenciana, Olearia argophylla, Pittosporum bicolor) and the tree-ferns (Dicksonia antarctica and Cyathea australis), usually 3–15 metres high, and the lower stratum (ground-layer) consists of ferns, sedges, wire-grass and herbs (e.g. Histiopteris incisa, Lepidosperma elatius, Pimelea axiflora, Polystichum proliferum, Pteridium esculentum, Tetrarrhena juncea and Viola hederacea. On the drier sites (e.g. northern slopes) Cassinia aculeata often forms an open but continuous shrub stratum (particularly soon after fire). Other shrubs that tend to become more prevalent in the later stages of regeneration may also be present (e.g. Olearia argophylla, O. lirata and Prostanthera lasianthos). The wetter sites usually support a denser and taller shrub-layer. Pomaderris aspera often forms a dense shrub stratum, interspersed with Cassinia aculeata, on wetter sites in the early stages of regeneration after fire. The understorey species soon increase in diversity. In general, the understorey becomes more dominated by ferns with age from the last fire (Ashton 1976) (Figure 6.19). However, the drier sites usually have a ground-layer that is dominated by Pteridium esculentum and Tetrarrhena juncea (Plate 6X). In the Toolangi, Powelltown and Toorongo districts, considerable areas of former Eucalyptus regnans forest have reverted to closed-forest of various Acacia spp. or scrub in which Cassinia aculeata, Dodonaea, and Pteridium esculentum are common. This is the result of repeated wildfires (Anon. 1973b; Gill, this volume).

Most of the Victorian Eucalyptus regnans forests are more or less even-aged (Figure 6.19). This has arisen following the destruction of seed-bearing trees by severe bushfires (Ashton 1976). This community is predominantly confined to the southern slopes of the Great Dividing Range, being common and widespread in the Acheron Valley and the Black Range, and on the Cerberean and Kinglake plateaus, and in the Dandenongs to Walhalla area. The lower limit of this community is at about 450 metres on the sheltered southern escarpments. Other occurrences are in the headwaters of the Bunyip, Latrobe, Thomson, and Yarra Rivers (Gullan et al. 1979). Characteristically it occurs on deep, friable brownish gradational soils; however, at lower elevations it occurs in reddish gradational soils derived from igneous parent rocks.

Damp forests

Eucalyptus obliqua and E. cypellocarpa-dominated open-forest (up to 40 metres high) is common throughout much of the region. Eucalyptus baxteri, E. dives, E. radiata and E. sieberi are often associated with this community. The understorey varies considerably but is usually a dense shrub-layer (e.g. Acacia mucronata, Cassinia aculeata and Daviesia ulicifolia) up to 3 metres high. The common sub-shrubs and ground-layer species include Billardiera scandens, Blechnum cartilagineum, Calochlaena dubia, Epacris impressa, Gonocarpus tetragynus, Goodenia ovata, Lepidosperma laterale, Lindsaea linearis, Lomandra filiformis, Platylobium formosum, Poa spp., Pteridium esculentum, Spyridium parvifolium, Stylidium graminifolium, Tetratheca ciliata, Tetrarrhena juncea and Viola hederacea.

Eucalyptus radiata forms an open-forest (28–40 metres high) at elevations of 300–1100 metres (rainfall of more than 1020 mm per annum) (Anon. 1972c, 1973a, 1974b). On cool moist sites it is frequently associated with Eucalyptus globulus or E. viminalis, and on drier sites it associates with E. dives, E. macrorhyncha and E. mannifera. The understorey often consists of scattered small trees or shrubs (e.g. Acacia dealbata, A. melanoxylon, Daviesia latifolia and Platylobium formosum). Pteridium esculentum and Poa spp. are common in the ground-layer. This alliance is common throughout much of the region (e.g. in the Darbyshire–Cravensville area—to the east of Tallangatta, in the Strathbogie Ranges, in the Mansfield area and on the Black Range).

Eucalyptus dives forms a shorter open-forest (15–28 metres high) on shallower, well-drained soils in usually drier areas (rainfall less than 890 mm or over 1140 mm per annum) than those that support the previous alliance. This species either forms pure stands or is associated with E. globulus or E. rubida. The understorey and ground-layer is similar to that of the E. radiata alliance. In moist areas, where the tree canopy reaches 25–28 metres in height, the understorey consists of scattered Acacia dealbata and Cassinia aculeata, usually with a Poa spp. and Pteridium esculentum ground-layer. The Eucalyptus dives alliance is common throughout much of the region, particularly on northern slopes and ridges (e.g. the area near the upper reaches of the Broken River, north-east of Mansfield).

Dry forests

Open-forest to woodland (up to 25 metres high), dominated by Eucalyptus goniocalyx, E. macrorhyncha, E. polyanthemos, E. obliqua and E. radiata, occurs on the relatively dry, undulating areas below elevations of about 400 metres. The understorey of sparse shrubs (up to 3 metres high) is dominated by Acacia mucronata, A. myrtifolia, Cassinia aculeata and Exocarpos cupressiformis. The sub-shrub- and ground-layer is usually dense. Common species include Gonocarpus tetragynus, Hypericum gramineum, Lindsaea linearis, Lomandra filiformis, Poa spp., Pteridium esculentum, Tetrarrhena juncea, Themeda triandra and Viola hederacea. Other species that are usually present include Acacia stricta, Acrotriche serrulata, Adiantum aethiopicum, Clematis aristata, Dianella revoluta, Pimelea humilis, Microlaena stipoides and Oxalis spp. This community occurs on clay-loam soils to the east of the Dandenong Ranges.

Eucalyptus goniocalyx and E. macrorhyncha dominate an open-forest (15–28 metres high) that is common to the south of Corryong (e.g. near Nariel Creek) and to the north of Mt Samaria (east of Lima South). It is also common in the neighbouring Midlands Region, in the Mt Granya area. This alliance is reduced to a low open-forest (usually less than 15 metres high) on drier sites (e.g. the Mt Mitta Mitta and Pine Mountain areas). In these forests E. dives usually grows 18–25 metres high. It either forms pure stands or is associated with E. goniocalyx or E. macrorhyncha (on dry ridges). The ground-layer is grassy with scattered sub-shrubs and herbs dominating (e.g. Burchardia umbellata, Daviesia ulicifolia, D. leptophylla, Grevillea alpina, Lomandra longifolia, Platylobium formosum, Stackhousia monogyna and Tetratheca ciliata) (Anon. 1973a).

Callitris endlicheri-dominated low open-forest

Low open-forests (less than 15 metres high) dominated by Callitris endlicheri occur on the granite massifs of Pine Mountain and Burrowa. Associated species are typical of a dry sclerophyll forest (e.g. Eucalyptus blakelyi, E. goniocalyx and E. macrorhyncha). Brachychiton populneus occurs occasionally as a co-dominant. Heathy shrubs (e.g. Calytrix tetragona) occur on shallow skeletal soils amongst the exposed rocks. This community also occurs in the neighbouring Midlands (e.g. Mt Pilot, Mt Porcupine).

Eucalyptus rubida/E. pauciflora-dominated low open-forest

A low open-forest usually less than 15 metres high, with Eucalytus rubida and E. pauciflora dominant, occurs along mountain ridges at elevations of 1160–1200 metres (e.g. at Mt Burrowa and east of Cravensville). E. dives is associated with this community on dry rocky sites (Anon. 1972c). The understorey is dominated by low shrubs (e.g. Bossiaea foliosa, Daviesia latifolia, Oxylobium ellipticum and Platylobium formosum). The ground-layer is characteristically dominated by Poa spp. (e.g. P. sieberiana).

Riparian forest

An open-forest occurs on the wet slopes and river banks of most of the major rivers in the region. Gullan et al. (1979) recognize this as riparian forest, however, the distinction from wet sclerophyll forest is not clear. This community is often dominated by Eucalyptus viminalis and sometimes by E. obliqua. Understorey species commonly include Acacia dealbata, A. melanoxylon, Cassinia aculeata, Coprosma quadrifida, Cyathea australis, Dicksonia antarctica, Goodenia ovata, Kunzea ericoides, Lomatia fraseri, Pomaderris aspera, Prostanthera lasianthos, Rubus parvifolius and *Rubus fruticosus spp. agg. The ground-layer is dominated by Acaena novae-zelandiae, Australina pusilla, Blechnum nudum, B. wattsii, Carex appressa, *Centaurium tenuiflorum, Centella cordifolia, Gratiola peruviana, Hydrocotyle hirta, Isolepis inundata, Lepidosperma elatius, L. laterale, Oxalis spp., Poa spp., Polystichum proliferum, *Prunella vulgaris, Pteridium esculentum and Viola hederacea. The liane Clematis aristata and the scrambling plant Tetrarrhena juncea are also common in this community. Examples of this association can be seen on the Acheron, Taggerty, Thomson and upper Yarra Rivers (Gullan et al. 1979) (Plate 6Y).

Land uses

Hardwood forests cover most of the public land in the region. These forest have been utilized for timber products since the earliest days of European settlement. Most of the common dominant eucalypts have been used as a hardwood resource. Pinus radiata plantations occur on private and public land (e.g. at Lake Eildon, near Kinglake, in the Acheron valley, near Stanley, and in the Ovens valley). Agricultural activities include animal production (e.g. beef, mutton, and wool) and plant production (e.g. tobacco, hops, vegetables, fruits and cut flowers). Orchards (e.g. apples, pears, plums, cherries and strawberries) and market gardens are common to the east of the Dandenong Ranges (e.g. near Silvan) (Anon. 1973b). Catchments south of the Great Dividing Range have been extensively used as Melbourne’s domestic water supply. North of the Divide, surface water has been used for irrigation (e.g. Lake Eildon). Much of the region is used for recreation such as bushwalking and canoeing.

National Parks

- Alpine (in part)—627 680 ha;

- Burrowa—Pine Mountain—18 400 ha;

- Dandenong Ranges (including Ferntree Gully)—1920 ha;

- Kinglake—11 430 ha;

- Mt Buffalo (only lower parts); 31 000 ha.

State Parks

- Avon Wilderness—40 000 ha;

- Bunyip (proposed)—13 830 ha;

- Cathedral Range—3580 ha;

- Eildon—24 000 ha;

- Moondarra—6290 ha;

- Mt Samaria—7600 ha;

- Wabba Wilderness—20 100 ha.

Source: Conn, B.J. (1993) Natural regions and vegetation of Victoria, in: Foreman, D.B. and N.G. Walsh (eds), Flora of Victoria Volume 1, pp. 79–158, Inkata Press.