Murray Mallee

The Murray Mallee as recognised by Conn (1993) includes the Murray Mallee, Murray Scroll Belt and Robinvale Plains regions in the current system of bioregions of Victoria.

The physiographic province described by the general term ‘Mallee’ refers to those semi-arid plains of south-eastern Australia characterized by extensive sand-ridges on which eucalypts with a particular growth habit (see ‘The mallee habit’ below) form the dominant cover (Bowler & Magee 1978). This Mallee province is here divided into two regions, namely the Murray Mallee and the Lowan Mallee Regions.

Location

The southern limits of the Murray Mallee Region forms a narrow zone in the Dimboola and Gerang Gerung area that separates the western and eastern parts of the Wimmera Region. The Little Desert of the Lowan Mallee Region isolates a small disjunct area of the Murray Mallee to the west of Horsham. The region extends beyond the Murray River (into New South Wales and South Australia) in the north to about the 33°S meridian of latitude, with more scattered occurrences extending towards Menindee (latitude about 32°30’S). In New South Wales this region occurs mainly to the east of the Darling River and then to the west of the Silver City Highway. In South Australia the northern limits approximate the northern boundary of the Dangalli Conservation Park, north of Renmark. Although no attempt has been made to map the exact extent of this region in South Australia, it extends north into the southern (particularly, south-western) part of the South Olary Plains environmental region of the Eastern province (Laut et al. 1977a, 1977b). The eastern boundary (in Victoria) is formed by the western limit of the current floodplain of the Avoca River, with the western boundary adjoining the eastern limits of the Lowan Mallee (the Big Desert and the southern parts of the Sunset Country). At latitude about 34°40’S the region extends westerly, from Victoria to just north of Nildottie on the Murray River in South Australia. It then includes the area between the eastern edge of the Mt Lofty Ranges escarpment and the Murray River as far south as Langhorne Creek in the Bleasdale environmental association of the south-east mallee environmental heathlands region in South Australia of Laut et al. (1977a, 1977b) and as far north as a latitude of about 34°S. There are several outliers, particularly in New South Wales. This suggests that the mallee communities have expanded and contracted with changes in climate (Beadle 1981). In Victoria outliers occur north of Bendigo in the ‘Whipstick Mallee’, and near Melton (Myers 1986).

In South Australia this region includes part of the Murray Mallee of Laut et al. (1977a, 1977b). However, a large part of that province is here included in the Lowan Mallee Region (see below). In New South Wales this region approximates to vegetation region ‘3A’ (Cameron, L. M. 1935), includes the southern part of the Far Western Plains (Anderson 1947, 1961) or South Far Western Plains (Jacobs & Pickard 1981). Although the boundary between the Far Western Plains and the (near) Western Plains is somewhat arbitrary, the southern limits of this boundary are a reasonable approximation to the eastern boundary of the Murray Mallee Region. Within Victoria the boundary between this region and the Wimmera is somewhat arbitrary because the vegetation has been extensively cleared for wheat cultivation.

For a summary of the information available on this region, refer to Cottington and Harris (1987).

Major grids A–C, E–H. Approximate area 32 044 km2.

Major landforms

The major landforms include an extensive undulating, mainly reddish clay to sandy plain that is often locally overlain by linear west–east aligned, stabilized sand dunes (Woorinen Formation, refer to Wasson in Noble and Bradstock 1989). In the eastern part of this plain, the surface is gently undulating with north–south to NNW–SSE aligned ridges (Hills 1939; Rowan & Downes 1963). It is thought that some of these are stranded coastal dunes formed during the retreat of the Tertiary Murray Sea (Blackburn 1962).

In general, mallee occurs on well-drained soils of coarse texture (see Gibbons and Rowan, this volume). Soils of fine texture, frequently associated with river systems, usually support woodlands rather than mallee. The only notable riverine landforms occur along the Darling, Murray and Murrumbidgee Rivers in the northeast part of this region (e.g. in Victoria, the Lake Hattah–Kulkyne area). All streams arise outside the region. The major riverine systems include the Darling, Murray, Murrumbidgee, Wimmera, Yarriambiac, Tyrrell and Lalbert. The last three creeks arise as effluents (outside the region) of the Wimmera River (Yarriambiac) and the Avoca River (Lalbert and Tyrrell). Freshwater lakes include Lakes Hindmarsh and Albacutya. There are several salt lakes, the largest of these being Lake Tyrrell.

The topography of the region is characterized by loosely compacted surface formations, all of which are below 200 metres altitude. A useful summary of the geology and physiology of this region is provided in Anon. (1987) and Wasson (in Noble & Bradstock 1989).

Climate

The region is characterized by a semi-arid climate with a mean annual rainfall of between about 400 mm in the southern parts and 220 mm in the extreme north. The small area that experiences a cool, relatively moist coastal climate in South Australia is characterized by a higher mean annual rainfall of about 500 mm. Since the region has a generally low relief with only minor topographical variation, little climatic change occurs across it. The wettest month is generally October, with the central and southern parts of the region having a high incidence of heavy summer thunderstorms, particularly during February. Droughts are a natural feature of the northern parts.

Much of the region experiences hot dry summers and mild winters, with temperatures slightly higher throughout the year in the northern parts. Frosts are common between May and September.

The winds usually are from the northern, western and southern sectors (see also ‘Climate of Victoria’, this volume).

Vegetation

The complexity of the vegetation in this region is illustrated by the floristic vegetation map in Anon. (1987, map 10) and Cheal and Parkes (in Noble & Bradstock 1989, figs 8.2 and 8.3). Frequently, the communities occur as complex mosaics. A summary of the vegetation communities is presented in the above two publications.

The mallee habit

Large areas of this region, extending into South Australia and New South Wales, are dominated by ‘mallee’ eucalypts. The term ‘mallee’ refers to a growth form, not to a particular eucalypt species (Specht 1972). These eucalypts are small (3–10 metres high), highly drought-tolerant trees that have a large underground lignotuber (‘mallee roots’). This lignotuber gives rise to several slender spreading branches or ‘trunks’ that terminate in a cluster of smaller branches with relatively sparse foliage. The largely buried lignotuber is protected from fires (Parsons in Groves 1981; Gill, this volume) and frosts (O’Brien et al. 1986). The importance of lignotuber regrowth, rather than regeneration from seed after burning or severe frost damage, is characteristic of many genera in the several families that occur in this region (Gardner 1957). Xanthorrhoea, a common component of the mallee—heath alliance (see below), has flower buds in apex and subterranean buds that are activated after fire (Gill, this volume).

Mallee communities

The most common mallee species in the region are Eucalyptus costata, E. dumosa, E. gracilis, E. leptophylla, E. oleosa and E. socialis. The canopy resulting from dense mallee communities is usually very even, and often approximately horizontal. Most mallee communities are structurally defined as open-scrubs (Specht 1970). Other small trees and shrubs that are frequently associated with this community include Acacia ligulata, A. rigens (both restricted to this region in Victoria), A. wilhelmiana, Callitris verrucosa, Dodonaea viscosa subsp. angustissima, Exocarpos aphyllus, Melaleuca uncinata, Olearia pimeleoides, Phebalium bullatum and Senna spp. All the Victorian species of Eremophila occur in this region. The herbaceous layer is usually discontinuous and is dominated by Triodia scariosa in the drier areas on infertile soils. Fertile soils support a ground-layer richer in grasses and herbs (e.g. Actinobole uliginosum, Danthonia setacea, Dianella revoluta, Goodenia willisiana, G. pinnatifida, Lepidosperma laterale and Stipa species). Ajuga australis is locally common under tall mallee or on sandy lake banks (e.g. Lake Hattah). With increasing aridity, salinity and/or calcium (limestone) content, semi-succulents (e.g. Crassula, Zygophyllum apiculatum and Chenopodiaceae) become progressively more important (‘Chenopod mallee’ sensu Anon. 1987). Short-lived annual herbs (ephemeral forbs) are often briefly common after rain. Eucalyptus gracilis, E. oleosa and E. socialis chiefly occur on brown loamy soils in relatively flat areas, whereas the other mallee eucalypts are more common on the white sandy dunes of the ‘Desert’ areas of the Lowan Mallee Region (see below). For a generalized summary of the mallee communities which occur on the aeolian soils, refer Hill (in Noble & Bradstock 1989). Soil texture and the often related availability of water has a significant influence on the composition of the species in stands (Willis 1943; Rowan & Downes 1963; Parsons & Rowan 1968; Noy-Meir 1974).

Eucalyptus dumosa, E. gracilis, E. oleosa and E. socialis characterize the most common mallee alliance which forms a mosaic with Acacia, Callitris (Adams 1985) and Alectryon oleifolius shrublands and low woodlands, and halophytic Chenopodiaceae-dominated shrublands.

Chenopod mallee

This community is common in the Sunset Country dunefields of the Woorinen Formation. It occurs in the red-brown soils of the swales. The overstorey is dominated by Eucalyptus gracilis and E. oleosa. The very open understorey is characterized by members of the Chenopodiaceae (e.g. Maireana pentatropis) and Zygophyllaceae (e.g. Zygophyllum aurantiacum, Z. apiculatum). The open ground-layer includes Chenopodium curvispicatum, C. desertorum, Enchylaena tomentosa, Maireana erioclada, M. radiata, M. sclerolaenoides, Omphalolappula concava, Ptilotus seminudus, Scleroleana diacantha, S. obliquicuspis and Stipa elegantissima (Anon. 1987).

East/west dune mallee

This community is common to the west of the Raak Plain and to the northern Sunset Country. It occurs on dunes with compact sandy-clay cores that are overlain by pale-orange sands. The overstorey is dominated by Eucalyptus costata, E. dumosa, E. leptophylla and E. socialis (Plate 6A). The open shrub-layer is characterized by Acacia rigens, A. wilhelmiana, Callitris verrucosa, Phebalium bullatum and/or Prostanthera serpyllifolia subsp. microphylla. The ground-layer consists of a more or less continuous sward of Triodia scariosa, and other herbs, particularly members of the Asteraceae.

Anon. (1987) and Cheal and Parkes (in Noble & Bradstock 1989) recognize a ‘shallow-sand mallee’ community which is intermediate between the Chenopod mallee of the swales and the east/west dune mallee and deep-sand mallee of the dunes.

Red-swale mallee

This community characterizes the heavy soils of the swales and plains that are strongly influenced by underlying sandstone. The overstorey is dominated by Eucalyptus calycogona, E. dumosa and/or E. socialis. The first two eucalypts commonly form a ‘whipstick’ subcommunity over large areas. The very open understorey commonly consists of Beyeria opaca, Dodonaea bursariifolia, Melaleuca lanceolata and Westringia rigida. The very open ground-layer characteristically includes Erodium crinitum, Maireana enchylaenoides, Plantago drummondii and Sclerolaena diacantha.

Big mallee

A community characterized by large, tall, mallee eucalypts (typically Eucalyptus behriana, E. porosa, and sometimes E. calycogona and E. dumosa) often occurs with red-swale mallee or on the margin of isolated grassy clearings. These eucalypts are also distinct because they have one or only a few thick trunks. The community occurs on heavy soils that have a strong underlying sandstone influence. The very open understorey is dominated by various chenopods (e.g. Chenopodium desertorum, Einadia nutans, Enchylaena tomentosa, Maireana enchylaenoides and Sclerolaena diacantha). Carpobrotus modestus and Senecio lautus are common components of the ground-layer.

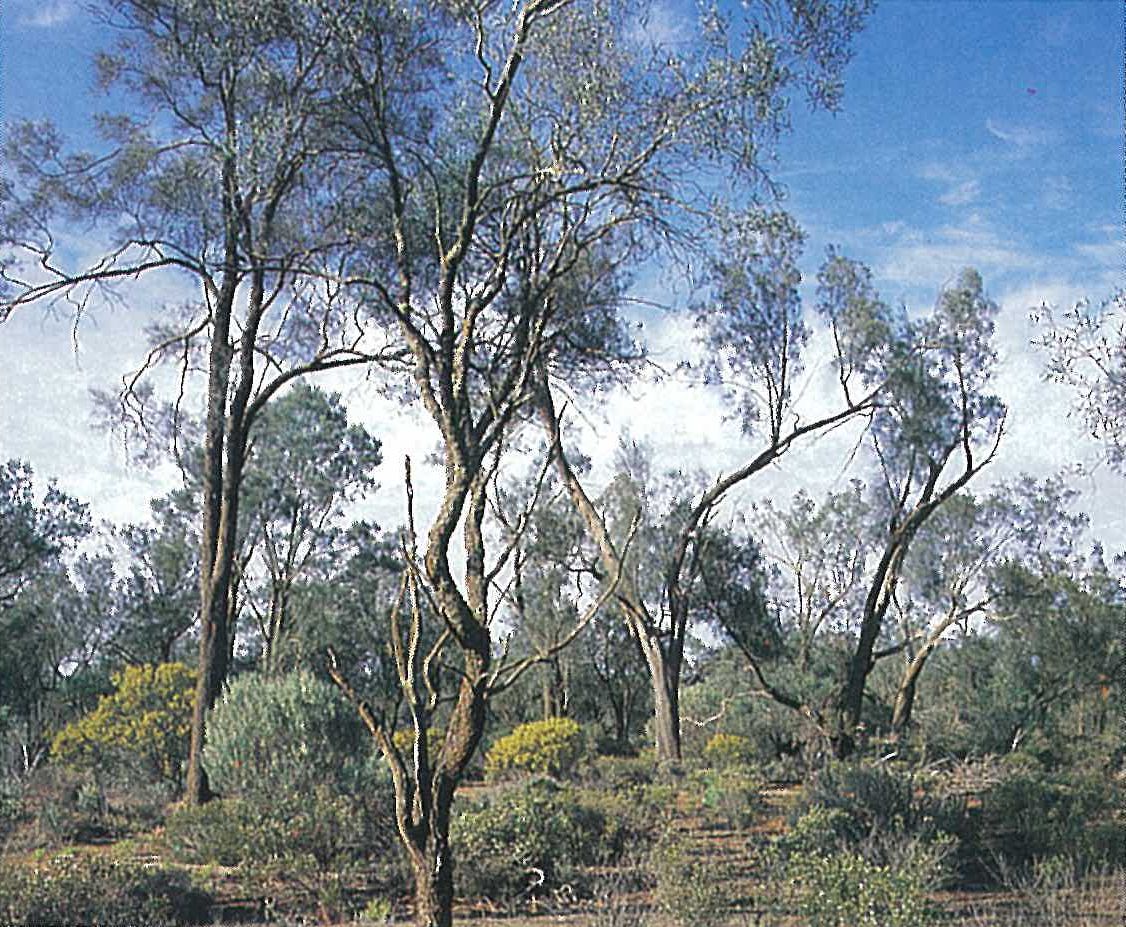

Belah woodland

Casuarina pauper (Belah) and, less commonly, Callitris preissii, often form an open-woodland community on the deeper, red-brown sandy soils of prominent old beach ridges. Associated species include Eremophila oppositifolia, Exocarpos aphyllus, Hakea leucoptera, H. tephrosperma, Myoporum platycarpum, Pittosporum phylliraeoides, Santalum acuminatum and S. murrayanum. A small shrub-layer, about one metre high, is characterized by Chenopodium curvispicatum, Eremophila glabra, Olearia muelleri, O. pimeleoides, Scaevola spinescens and Senna artemisioides. The ground-layer consists of sub-shrubs, perennial tussock grasses and other herbs. This community is best developed in the Yarrara Block of the Munray–Sunset National Park, a few kilometres north of the Sunset Country (Plate 6B). There is a smaller occurrence at Robinvale.

Unlike the mallee eucalypts, Callitris species are killed by fire and regenerate solely from seed. Extensive grazing of Callitris seedlings by rabbits and the deaths by fire have severely reduced the amount of regeneration of these species.

Pine–Buloke woodland

This community is dominated by Callitris preissii (Pine) and/or Allocasuarina luehmannii (Buloke). It occurs on lunettes associated with lake beds and creek systems. Although the former species typically occurs on deep sands and the latter species on heavier loams, both also occur together over broad areas (Anon. 1987). All examples of this community are disturbed to a greater or lesser extent. The open understorey is characterized by Acacia oswaldii, Pittosporum phylliraeoides and Santalum acuminatum. The ground cover was apparently once dominated by perennial tussock grasses and herbs (Anon. 1987). These have been largely replaced by several introduced species, for example, Brassica tournefortii, Hypochoeris glabra, Medicago minima, Silene spp., Trifolium spp. and Vulpia bromoides. This community occurs in the Hattah–Kulkyne National Park.

In the far north-west of the region, near the Murray River, Callitris glaucophylla replaces C. preissii as the dominant tree species on lunettes. However, this community is very rare in Victoria.

Grassy woodland and grassy mallee

These communities are often inappropriately referred to as savannah woodland and savannah mallee, respectively; however, the word ‘savannah’ refers to tropical grassland with scattered trees and palms, and so is not used here. Typically, these communities are very disturbed. The overstorey may be scattered or absent. These communities may be anthropogenic rather than ‘natural’ (Anon. 1987) because both occur in heavily grazed areas (e.g. in evaporation basins and the fringing area of the alluvial plain).

Woodlands with a grassy ground-layer have an overstorey of scattered Callitris preissii and Alectryon oleifolius. The overstorey of this mallee community consists of scattered Eucalyptus gracilis and E. socialis. The ground flora consists of alien plants. These include Brassica tournefortii, Critesion murinum subsp. glaucum, Medicago minima, Schismus barbatus, Sonchus oleraceus, Urtica urens and Vulpia spp.

Floodplain woodlands and forests

The floodplains of the more significant river systems support a Eucalyptus camaldulensis (River Red-gum)–E. largiflorens woodland to open-forest. The latter species usually occurs on the flat plains at a slightly higher level than E. camaldulensis. The soil is characteristically a grey clayey loam, usually with a well-contrasted profile differentiation (essentially duplex in structure). This community is also described for the Lowan Mallee and Riverina Regions.

Black Box–chenopod woodland

The Murray River floodplain is characterized by a Eucalyptus largiflorens (Black Box) woodland with a Chenopodiaceae understorey (e.g. Chenopodium nitrariaceum, Enchylaena tomentosa and Rhagodia spinescens). The understorey is frequently dominated by Muehlenbeckia florulenta (e.g. at the southern edge of Lake Hindmarsh). Chenopods also dominate the ground-layer.

Black Box wetland

In areas of alkaline gilgai soils (see Gibbons & Rowan, this volume) that are periodically flooded (e.g. Yarriambiac Creek floodplain, Connor 1966a), the Eucalyptus largiflorens (Black Box) alliance typically lacks shrubs. However, a dense herbaceous ground-layer of rushes and sedges is common. The common species include Eleocharis acuta, E. pusilla and Juncus flavidus. Danthonia duttoniana, Enteropogon acicularis and Eragrostis lacunaria are more common on the drier sites.

River Red-gum forest

Eucalyptus camaldulensis (River Red-gum) dominates an open-forest, often with an open understorey of Acacia salicina or A. stenophylla. The ground-layer commonly includes Alternanthera denticulata, Centipeda cunninghamii, Chamaesyce drummondii, Cyperus gymnocaulos, Paspalidium jubiflorum and Wahlenbergia fluminalis.

Good examples of this forest occur along much of the Murray River in the north-west of the state.

Grasslands

Natural grassland areas are poorly developed. Bromus arenarius and species of Chloris, Danthonia, Eragrostis and Stipa are common. Many of these communities have been invaded by alien species.

Sandplain grassland

Examples of this community occur in the sandy soil of old evaporation basins of the Sunset Country. Grazing by sheep has resulted in the establishment of several alien species. The dominant grasses of this grassland are Aristida contorta, Stipa drummondii and S. eremophila. The other common herbaceous species include Hyalosperma semisterile, H. stuartianum, Leptorhynchos waitzia, Minuria leptophylla, Podolepis canescens and Rhodanthe pygmaea.

Gypseous plains grassland/gypseous rise woodland

The grassland communities that occur on the gypseous plains (copi) of the far north-west of the Sunset Country are heavily grazed by sheep. All examples of these communities in Victoria are extremely disturbed, and their original composition can only be inferred. Anon. (1987) suggests that the semi-arid woodland present in South Australia may approximate to the gypseous rise woodland. The common herbaceous species include Brachyscome lineariloba, Bromus rubens, Daucus glochidiatus, Erodium crinitum, Goodenia pusilliflora, Hypochoeris glabra, Medicago minima, Sonchus oleraceus and Stipa scraba group. The low shrubs of Sclerolaena diacantha and S. obliquicuspis are the last shrubs to disappear from heavily grazed areas (Anon. 1987).

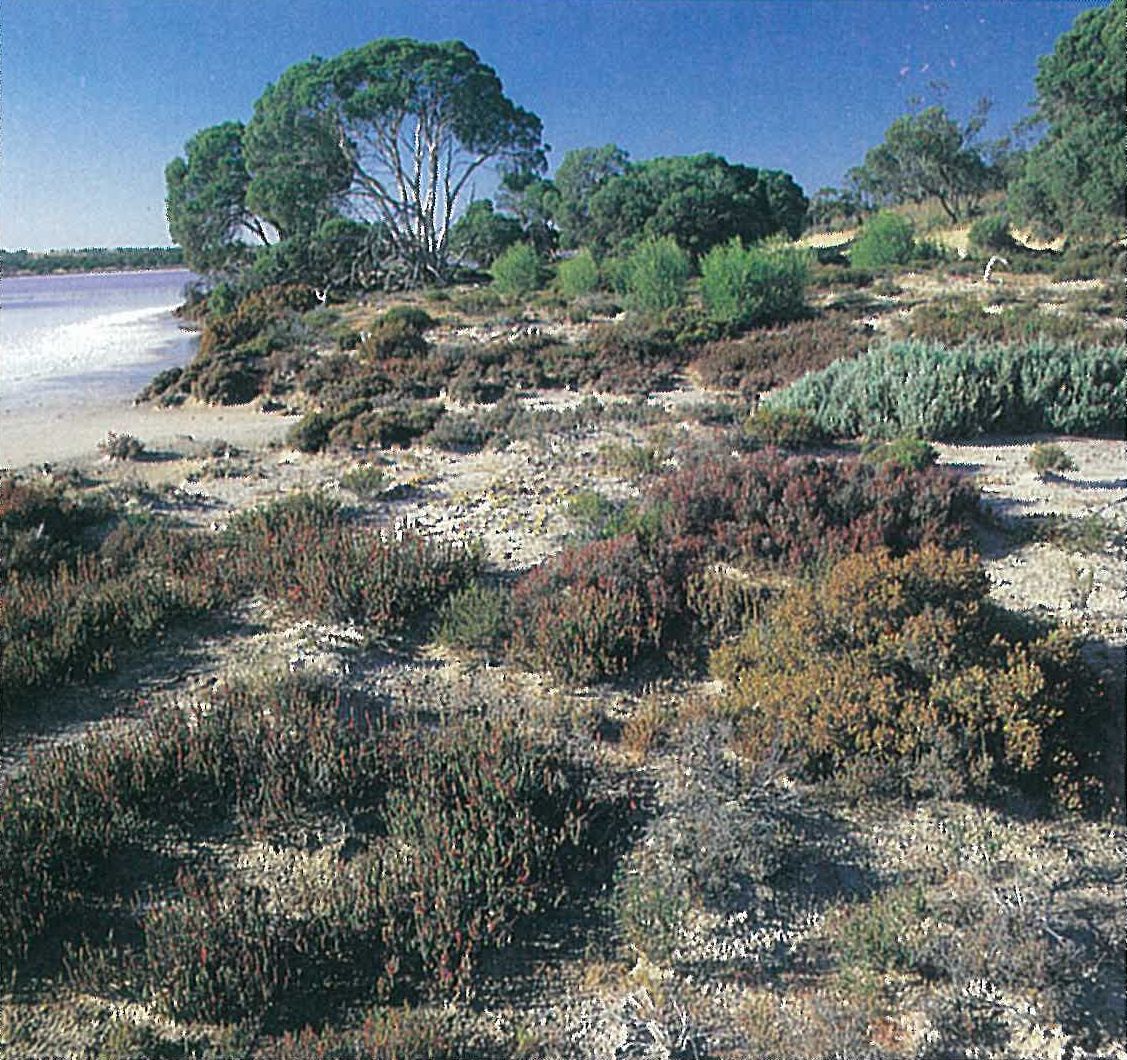

Halophytic shrubland

With the exception of the Darling–Murray–Murrumbidgee river system, the rivers in this region terminate in inland ‘lakes’ that are usually dry and are referred to as ‘playas’. The playa bed is either clayey (clay flats) or salt-encrusting (salt pans). Small playas and those that are regularly flushed out by floodwaters have a saline or subsaline clay substrate, usually overlying gypseous clays.

Many salt lakes (e.g. Lake Tyrrell), salt pans, gypsum (copi) and clay flats occur throughout this region, with the greatest development in the north of the state (between Mildura and Boundary Point) and adjoining the floodplain forest of the Murray. The northern plains support bluebush shrubland (Maireana pyramidata–M. sedifolia) on sandy soil that has a reasonably high lime content.

Large copi deposits occur near Cowangie (north-east of Murrayville), on the South Australian–Victorian border south of the Sturt Highway, and to the west of Lake Hattah in the Raak Plain. These are the sites of old lakes that have dried up (Hills 1940).

The type and density of vegetation on saline playas is determined by the salt concentrations, which, in part, is determined by the season. When crystalline salt is visible on the surface, the vegetation is retricted to the surrounding higher land. The most salt-tolerant species belong to the Chenopodiaceae, particularly the samphires or glassworts (namely Halosarcia, Pachycornia and Sclerostegia), but also Atriplex, Maireana and Sclerolaena. Other salt-tolerant plants include Frankenia, Disphyma crassifolium subsp. clavellatum and Zygophyllum (Plate 6C). Several annual Asteraceae are also common.

Alluvial-plain shrubland

The broad alluvial terraces that occur along the Murray River to the west of Mildura, support an alluvial-plain shrubland. This area is also devoid of trees.

The dominant low shrub-layer is predominantly composed of members of the Chenopodiaceae. The common species include Atriplex vesicaria, Sclerolaena divaricata and S. tricuspis. The ground-layer is characterized by Disphyma crassifolium subsp. clavellatum and several native and introduced herbs (e.g. Brachyscome lineariloba, Crassula colorata, Pogonolepis muelleriana and Senecio glossanthus). Areas that are more affected by saline groundwater usually support Halosarcia pergranulata and Parapholis incurva. Most areas are subject to sheep-grazing.

A more diverse Chenopodiaceae-dominated shrubland (the ‘Alluvial-rise Shrubland’, sensu Anon. 1987) occurs on the red-brown sandy-loam rises that are scattered on the alluvial plain. The shrub-layer is usually dominated by Maireana pyramidata to about one metre high. Occasionally Atriplex nummularia or Maireana sedifolia are also present. The ground-layer includes scattered Atriplex lindleyi, Malacocera tricornis, Sclerolaena brachyptera and S. tricuspis. This shrubland is usually more degraded by grazing than the alluvial-plain shrubland.

Lake-bed communities

The type of community that is present on lake beds is dependent upon the soil type and the time since inundation (Anon. 1987). In the first few seasons after a flood, the dried-out lake beds are usually dominated by tall native herbs (e.g. Agrostis avenacea, Glycyrrhiza acanthocarpa and Lavatera plebeia). Increased grazing pressure between flood periods usually results in the introduction and establishment of alien species (e.g. Bromus spp., Critesion spp., Hypochoeris glabra, Medicago spp. and Trifolium spp.) (Anon. 1987).

Land use

This region has been extensively cleared for the cultivation of cereal crops and grazing. Much of the region receives additional supplies of water via the gravitational-feed channel system. Approximately half of the water for the Wimmera–Mallee domestic and stock water supply originates in the Grampians (Calder, J. 1987). Irrigation along the Murray River has enabled the establishment of orchards and vineyards in the Mildura–Red Cliffs area. The other additional supply of water, other than rainfall, is from artesian bores. The National and State Parks ensure the conservation of the remaining native flora and fauna.

National Parks

- Hattah–Kulkyne (in part)—48 000 ha;

- Murray–Sunset (in part)—633 000 ha.

Source: Conn, B.J. (1993) Natural regions and vegetation of Victoria, in: Foreman, D.B. and N.G. Walsh (eds), Flora of Victoria Volume 1, pp. 79–158, Inkata Press.